Brussels, 04/10/2006

Says ETUC General Secretary John Monks: “If the euro area is to experience continued growth, then the recovery needs to become self-reliant. European workers need a raise, and the ECB must realise that reasonable wage increases are part of the solution and not part of the problem.”

The ECB is justifying its monetary tightening by referring to ‘higher than expected wage increases' triggering second-round effects from high oil prices and planned hikes in indirect taxes. However, a study by the ETUC comes up with different findings.

There are no major second-round effects or upward risks to price stability to be expected from wages:

Recent wage agreements, running well into 2007, do not show any sign of a general acceleration. Even well publicised agreements, after closer examination, are not an exception to this rule. For example, the German steel sector pay deal of 3.7% over 17 months may look spectacular, but it merely represents a moderate 2.6% increase on an annual basis.

Given the fact that wage formation in Germany is especially reactive to economic conditions and that many wage agreements there are up for renewal well after the impact of indirect taxes on inflation will have petered out, a price-wage spiral in Germany is very unlikely.

Where automatic wage indexation systems still exist in the euro area, rules exist to keep inflationary developments well under control. For example, since the 1993 incomes agreement in Italy, national guidelines on price compensation in wages systematically take into account the objective of price stability and low inflation.

On the contrary, as far as wages are concerned the risks relate to downwards pressure on growth:

The ETUC study stresses that not every acceleration of wage growth should be seen as an inflationary problem. With wages growing at the moment by 2.5%, the upper limit for inflationary wage growth, estimated at around 3.5-4.5%, is ‘light years' away.

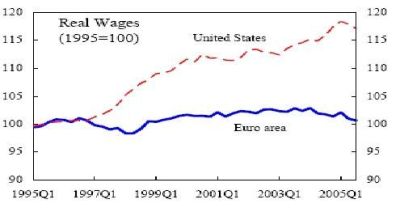

Moreover, the Phillips curve (defining the relationship between the rate of unemployment and the rate of inflation) is dead in the euro area (see graph below). Experience over the last decade shows that, despite a trend of falling unemployment, wage formation remains almost flat, in downturns as well as in upturns. With the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimating that an additional 1% of demand-driven growth only results in 0.2% extra wage increases, it may indeed take a very long time before the limit for inflationary growth is reached.

If wages accelerate less than the ECB expects while substantial monetary support is withdrawn from the recovery at the same time, the present expansion may turn out to be short-lived again, and a renewed downturn may be around the corner.

{{Does the Phillips curve still exist in the euro area?

}}

Source: IMF