Brussels, 07-08 December 2006

1. The need to strengthen the European dimension of collective bargaining: Wages and working conditions under pressure from the European Economic Model

The management of economic and monetary integration in Europe is posing important challenges to the collective bargaining. It is getting clearer and clearer that collective bargaining no longer takes place in a national vacuum but is at the same time dependant on as well as influencing bargaining practices in other European countries. The European economic model is turning collective bargaining into a matter of common concern for trade unions throughout Europe:

- Unlimited capital mobility in the European marketplace is used to set up a de facto coordination of business demands. Concession bargaining deals are efficiently ‘exported' by putting workers and trade unions in other member states under pressure to deliver similar concessions in return for the promise of maintaining local investments.

- With the macro-economic policy regime not providing sufficient aggregate demand to sustain high and continuing growth rates, in particular in the euro area, member states are embarking on ‘beggar-thy-neighbour' policies. In an attempt to secure more growth for themselves by pinching investment from others, competitive wage moderation is triggering a vicious circle of weak domestic demand leading to low overall growth, thereby setting the stage for a next phase of concessions from workers.

- In all of this, the European Central Bank is reacting in an alarmist way : An imaginary revival of wages, even from an extremely low pace of growth, is used as an alibi to hike interest rates, thereby running the risk of weakening the economic recovery as well as the bargaining position of workers

- Competitive imbalances inside the euro area are building up. Unit wage costs are stagnating in some members but have been increasing since 1999 by around 30% in others. Since the devaluation of the currency is no longer an option, the risk is that collective bargaining in the latter countries sooner or later becomes under heavy pressure to deliver outright cuts in nominal wages.

- Meanwhile, high level representatives from the European Central Bank are openly advocating ‘ex post' and profit related compensation systems instead of collective bargaining with ‘insiders'.

- But also outside the euro area, wages and working conditions are under risk from the European Economic Model. Constrained by the European fiscal framework to reduce deficits while at the same time having to build up the stock of public capital, some Central and Eastern European countries may come under pressure to slow down the pace of increase in public sector wages and minimum wages. These are however the main drivers for overall wage growth in these countries.

In addition, the framework of reference for big companies is increasingly shifting from the national sectoral level towards the European level or even the global market on which these companies are competing, thereby putting pressure on nationally determined working conditions.

With wages and working conditions becoming the only factor available for economic policy to steer the national economy against a background of an insufficient dynamic European internal market, there is the risk that governments try to achieve this kind of excessive wage flexibility (for example substantial cuts in nominal wage levels) by weakening trade unions, collective bargaining institutions and workers' rights.

Given the nature and extent of these challenges, the ETUC needs to reinforce the coordination of collective bargaining in Europe. The reasons why the Helsinki congress set up the coordination of collective bargaining (avoid competitive wage moderation, ensure wages receive a fair share of economic benefits, ensure upward wage convergence in enlargement) are more valid than ever.

To strengthen the coordination of collective bargaining the ETUC will endeavour to:

- Intensify the exchange of information on ongoing collective bargaining. In order to address business coordination efforts to spread concession bargaining throughout Europe, all of us all need information ‘in real time'. The ETUC will continue with the collective bargaining bulletin, which was restarted in 2006. We will also work to establish a web site containing overview statistics and the latest collective bargaining outcomes and only accessible to members. Furthermore, in cooperation with the ETUI-REHS, a databank on transnational bargaining agreements will be established.

- To have access to information ‘in real time', a network of collective bargaining experts will be established by maintaining a closer contact with those responsible in European federations and national affiliates for the coordination of collective bargaining will be established . To do so we call upon members to look into the possibility of associating representatives from the ETUC in eventual coordination meetings at national or European/sectoral level.

- Take a more offensive stance by highlighting in the European public opinion and policy discussion those agreements representing major achievements in improving working conditions for workers.

- Support and multiply trade union initiatives of cooperation such as the Doorn group to build stronger awareness of and a strategy towards common challenges to collective bargaining in a Europe of economic, territorial and monetary integration.

2. Bargaining outcomes over 2006

Nominal wage developments in Europe diverge over 2006, according to the ETUC questionnaire on collective bargaining. Nominal bargained wage increases range from a low of 1.5% to almost 4% in some central European countries (Czech Republic, Poland) as well as Norway, with Slovakia realising a 7.7% increase. In Germany and the Netherlands, these low nominal wage increases translate into a fall in the purchasing power of negotiated wages.

Shifting the analysis to the total growth in wages, robust increases in real terms are to be found in the central and eastern member states and in Scandinavian countries while real wage increases are near zero or even negative in euro area member states.

An evaluation of these wage developments on the basis of the ETUC formulae concludes that wage moderation continues in Europe. With a few exceptions, no single country reported in the questionnaire achieves such a wage growth in line with inflation and productivity. In other words, the share of wages in total revenue continues to fall in Europe.

{{

3. Social and economic perspectives for 2007}}

Growth in the EU 25 in 2006 surprised on the upside and, driven by an acceleration of growth in the euro area and the UK, jumped from 1.7% in 2005 to 2.8% to 2006, a growth rate not seen in many years and very close to the average growth rate of the strong 1997-2000 business cycle. As a result, employment increased by 1.4% and unemployment fell significantly from 8.6 to 8%.

However, prospects for 2007 and 2008 already indicate another turnaround in growth. With fiscal and monetary policy taking aggregate demand back out of the economy, the European Economic model is working to bring the rate of economic expansion back down to 2.1%(euro area) or 2.4% (EU-25). Unemployment would only edge down slightly over the next two years, from 8 to 7.4%.

However, modest economic growth together with modest falls in unemployment will not work to provide a stronger basis for wage bargaining to turn around wage moderation into reasonable but robust real wage increases.

At the same time, there is an imbalance in the policy equation and a risk that growth turning might turn out to be much weaker than currently expected. With the ECB expecting a significant and inflationary acceleration of wages there is a risk of exaggerated monetary overshooting of the ECB,if wage growth does not accelerate at all, as is likely to be the case. But the real risk is not one of too high wage increases but one of too low wage developments than expected.

4. Guidelines for the 2007 negotiations

4.1 Collectively bargained wages

Against this background, the ETUC calls upon its members to focus 2007 wage bargaining strategies on the guideline of orienting wage growth in line with the sum of inflation and productivity growth. This guideline remains valid to pursue and combine the different objectives of guaranteeing wage owners a stable share of the economy's total income, of supporting economic activity and job growth by providing households with the financial room to increase consumption and of avoiding cost-push developments that would imply a return to inflationary threats. In particular for the euro area, the guideline is more than ever valid to avoid an outcome in which neither monetary policy through interest rate nor worker's purchasing power is supporting demand and overall growth in the economy.

The ETUC guideline on average wage growth needs to be implemented, taking into account the different productivity trends and the different settings for price stability in the member states.

The situation of low wage earners remains a concern. Some 15% of workers in Europe are working below two thirds of the national median wage, with a share going as high as high as almost 20% in some countries. The ETUC calls upon affiliates to pay specific attention to fighting low pay and poverty wages by developing ‘solidaristic' wage bargaining strategies. Interesting examples are to be found in Austria [[The recent concluded collective agreement in Austrian metal provides an illustration. The sector agreement defines a 2.6% wage increase from which a company agreement can deviate through a redistribution agreement: 0.5% of a company's wage bill can be mobilised to give an extra increase to lower income groups, favouring women in particular provided the across-the-board rise is no lower than 2.4%.]] , where a certain part of the total room for wage increases can be reserved for distribution amongst the lower paid and in Nordic countries, Belgium and Italy where negotiated wage increases are expressed in absolute amounts rather than in percentage increases, thereby moving low paid workers gradually upwards.

4.1.1 Wage bargaining and gender wage differences. *

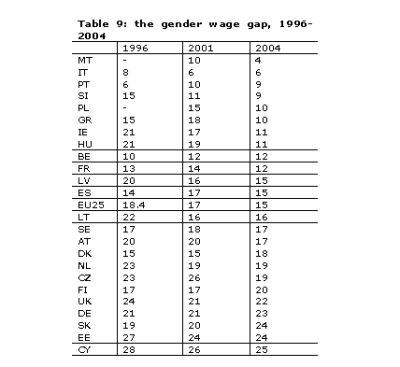

One of the persistent features of wage structures in Europe is that there is still a gap between the wages men and women receive. In 2004, according to Eurostat data, this gap was 15 percent (Table 9).

The good news here is that over the years there has been an improvement: in 2001 the gender pay gap was still 17 per cent and in 1996 it was 18.4 per cent. At the same time, improvements are slow and the gap remains substantial. Also, in several countries the gap has been increasing in the last years.

The gender pay gap is partially is the result of a series of factors, including the sectoral and occupational segregation of the labour market, overall wage inequality, educational differences, labour market participation rates, and straightforward discrimination. For example, the countries in which the gender pay gap is low are not necessarily countries where men and women are treated equally; in most cases they have low female participation rates, and the relatively small group of women that is in the labour market is often relatively highly educated and in relatively well-paid jobs. In other countries, high participation of women is often concentrated in low-paid service occupations, leading to a larger pay gap. In some countries human capital differences explain a major part of the gender pay gap (for example, 41.6 per cent in Belgium) but and in others only a small part (for example, 6.4 per cent in Denmark)[[On these issues, see ETUI/ETUC (ed.) Benchmarking Working Europe 2006, Brussels (chapter 4); Plasman, R. and Sissoko, S. (2004) Comparing Apples with Oranges: Revisiting the Gender Wage Gap in an International Perspective, IZA Discussion Paper 1449, Bonn: IZA]].

Gender equality has traditionally been a key issue for trade unions in Europe. Still, it is only marginally addressed in wage bargaining in Europe. For most trade unions gender equality is a political objective but this is often not reflected much in their bargaining strategies or in bargaining results and the gender pay gap is reported to have been decreasing only slightly.

{Note: The gender pay gap is given as the difference between average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees and of female paid employees as a percentage of average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees. The population consists of all paid employees aged 16-64 who are 'at work 15+ hours per week‘.

Source: Eurostat}

There are some exceptions to this general trend. For example, in Finland, a gender equality allowance is paid in 2006, aimed at increasing wages in sectors that employ large numbers of women. Also, in Norway, in the state/government sectors guidelines were established for collective bargaining to give women a bigger share of the wage increases negotiated. In addition, in Denmark, equal pay statistics are elaborated to make the gender pay gap more visible.

4.2 Qualitative working conditions

The ETUC report on precarious work (see annex 1), based on the information provided by affiliates, and concludes that many labour markets in Europe are confronted with situations of ‘excessive flexibility'. Business, using global competition as an alibi to increase profits further and boost CEO to immeasurable heights is forcing vulnerable workers such as youngsters, women, long term unemployed and migrants into insecure jobs with poverty wages and long working hours without offering prospects for upwards transition (low access to training, limited career development). In Europe as a whole, already half of all new contracts are fixed-term, temporary contracts with this share increasing to 80% in particular countries. In other countries, the share of temporary jobs in total existing jobs runs as high as 33%. However, an insecure workforce is not a productive workforce open to innovation. A modern labour market has no place for precarious work practices.

The ETUC requests national affiliates and industry federations to undertake special efforts in 2007 in order to reduce and control precarious work practices. The ETUC draws members' attention to existing good practices and principles to do so:

- Rewarding good employer behaviour and sanctioning bad work practices by modulating employer social security contributions whether open ended or temporary work contracts are used, as proposed in the Italian budget.

- Closing loopholes in labour law used by employers to keep workers trapped in endless chains of temporary contracts, as for example in the recently concluded tri partite agreement in Spain [[See Collective Bargaining Bulletin 2006/3, based on information received from UGT-E]].

- Limiting precarious work practice through collective bargaining agreements limiting the share of a-typical workers in companies and/or the time spell during which workers can be hired on a temporary basis.

- Promoting an equivalent rights approach making sure a-typical workers have access to social security, holiday (pay), training and lifelong learning.

In a globalising world, labour market institutions need to ensure upwards flexibility and upward mobility of workers. A modern labour market provides access to training for all workers. However, the European labour market scores badly on this issue. Business is paying much lip service to the importance of training.

In practice however, business is under investing in training while the access to training is almost blocked for those who are the most in need of it (low skilled workers, older workers, long term unemployed, temporary workers).More than 70% of workers do not receive any training paid for or provided by their employers. Moreover, the trend is negative in the EU-15 [[No comparative figures available for EU-25]]. Compared to 2000, the share of workers receiving training has fallen from 30% to 27% in 2000, with business in the Central and Eastern European countries training as little as 6-10% of their staff. In addition, the number of average number of training days per worker has fallen as well from 14 days to 11 days a year. Only 10% of workers with a primary level of education receive training compared with 40% of those with third level education [[Figures from EIRO : Fourth European Working Conditions Survey]].This dismal situation needs urgent change.

Globalisation and European integration can only work for all if markets are equipped for positive change by continuous up skilling of the work force. Following up on the EMF 2005 initiative to set up a common demand on the right to training of five days a year for each worker, the ETUC will engage with affiliates in order to see whether such a common demand would also be possible on the ETUC level. As a first step, the ETUC will request affiliates to report on the situation of training provided by enterprises on the collective bargaining strategies they use to promote business investment in a skilled workforce, thereby ensuring that all workers have access to training. To this end, the ETUC will request affiliates to present a report for the first collective bargaining committee in 2007. Furthermore, the ETUC draws members' attention to sectoral and/or intersectoral agreements which correct the market failure and business underinvestment in training by obliging all firms to contribute to social partner funds which have training of workers as an objective with a special focus on groups at risk in the labour market.

Finally, the ETUC confirms its attachment to policies ensuring quality at work. This implies, besides fair and decent wages, access to training and secures work contracts, health and safety at work, gender equity and mainstreaming and environmental friendly jobs. In this respect, the ETUC draw attention to the fact that work intensity, working to tight deadlines or working at high speed is rising, from 35% for the EU12 in 1990 to 46% of the EU-25 workforce in 2005.Concerning health and safety, 25% of workers in the EU-15 considers their health at risk because of their work, whereas this percentage jumps to 40% in the new member states.

5. The trade union initiative for a European framework for cross-border negotiations

5.1- Transnational mobility of businesses and MNGs at European and extra-European level is constantly increasing.

This activity has, until now, occurred outside the framework of the rules and procedures for transnational negotiation, and this raises a problem for the Union at all levels in terms of the social management of these processes.

Account does need, however, to be taken of the fact that by the end of last year, almost a hundred texts had already been signed (see annex 2 page 5-7 in French), with an increase latterly in both the quantity and the content of the agreements.

Most of these agreements look at the European dimension, but these texts have been signed by the most diverse players, including the EWCs, which, as the legislation stands at present, have no right of negotiation, with the risk of weakening the negotiating power of the Union at every level.

For these reasons, the ETUC confirms that the Commission's initiative, under the social agenda for 2005-2010, to grant an optional legal value, in other words, at the disposal of the social partners, is a response to an unquestionable need.

The Commission recently has announced the opening of the formal consultation of the social partners for the coming year.

5.2- It is quite obvious that the EIFs and the Unions involved at national level have the prime responsibility for the definition of the rules and the processes for the negotiation and management of these agreements. In order to allow the concrete management of these processes, it is quite clear that this definition of the rules and procedures within the Union applies beyond the Commission initiative.

5.3- In this framework, the ETUC's role relates to the definition of the principles and the general reference conditions targeted to support and reinforce this action.

As things stand, we want to reconfirm the three key conditions which were already debated and approved by the EC of 5th and 6th of December 2005.

5.3.1 The individual definition of the players involved and their representativeness. For the ETUC, this representativeness is granted solely to the trade union organisations, in their capacity as collective representatives, which might also involve some legal effects.

Accordingly, the right to issue a mandate to negotiate and the right of signature must remain rights strictly belonging to the trade union organisations.

5.3.2 The content and the effects of the agreements concluded at this level cannot mean a downwards levelling of the clauses already negotiated in the collective bargaining agreements and in the national legislation. Accordingly, a non-regression clause needs to be clearly stipulated.

Just as the ETUC reaffirms that this new level must be integrated and enrich the global negotiation framework available to the social partners, without modifying the competences and powers already existing at national level.

5.3.3 The management of any conflicts of interest during the negotiation or the implementation of the agreements. The ETUC reaffirms the need for the definition of a coherent framework to allow transnational collective bargaining, including the recognition of rights such as the right of association and the right to strike.

At the same time, the ETUC reiterates its demand for the creation of a section dedicated to the problems of labour close to the European Court of Justice, with the inclusion of the experts appointed by the social partners, in order to allow for a potential intervention in the event of the foundering of the conciliation procedures between the partners who have signed up to an agreement.